Search and Destroy: Engineering T-Cells to Find and Kill Cancer

At Oxford Global’s 2021 Immuno Week: Online, we heard from an exciting array of experts in immuno-oncology. Among them was a fascinating presentation that showcased how T-cells can be engineered to improve their success in finding and killing cancer cells.

The presentation was led by Oliver Zill of Init Biosciences, who was then Computational Biology Lead of the TCR-T (TCR-edited T-cells) program at Genentech. Zill explained how at Genentech they were taking advantage of the cells’ own T-cell receptors, alongside other clinical developments in T-cell augmentation (such as the promising CAR-T therapy).

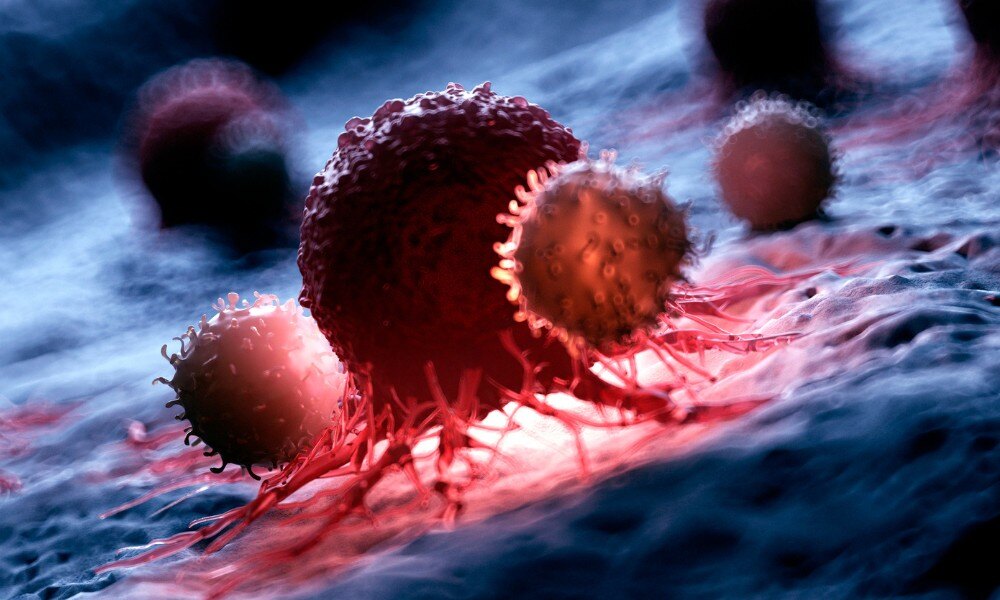

Like a police force of the immune system, T-cells constantly patrol their environment in the body, looking for mutated cancer cells. They do this by looking for unexpected antigens on the cancer cells’ surface, expressed on their MHC-Class I molecules, like checking a face against a mugshot.

If the T-cell finds an antigen that does not look right, like one associated with a cancer cell, it triggers an anti-tumour immune response to destroy the cancer. The tumour cell’s mugshot is its T-cell receptors (TCRs) on the surface of the T-cells; this is how the T-cell recognises the tumour antigen. If a TCR connects to the antigen, cytotoxic granules are then injected into the tumour cell, killing it.

T-cell Therapy

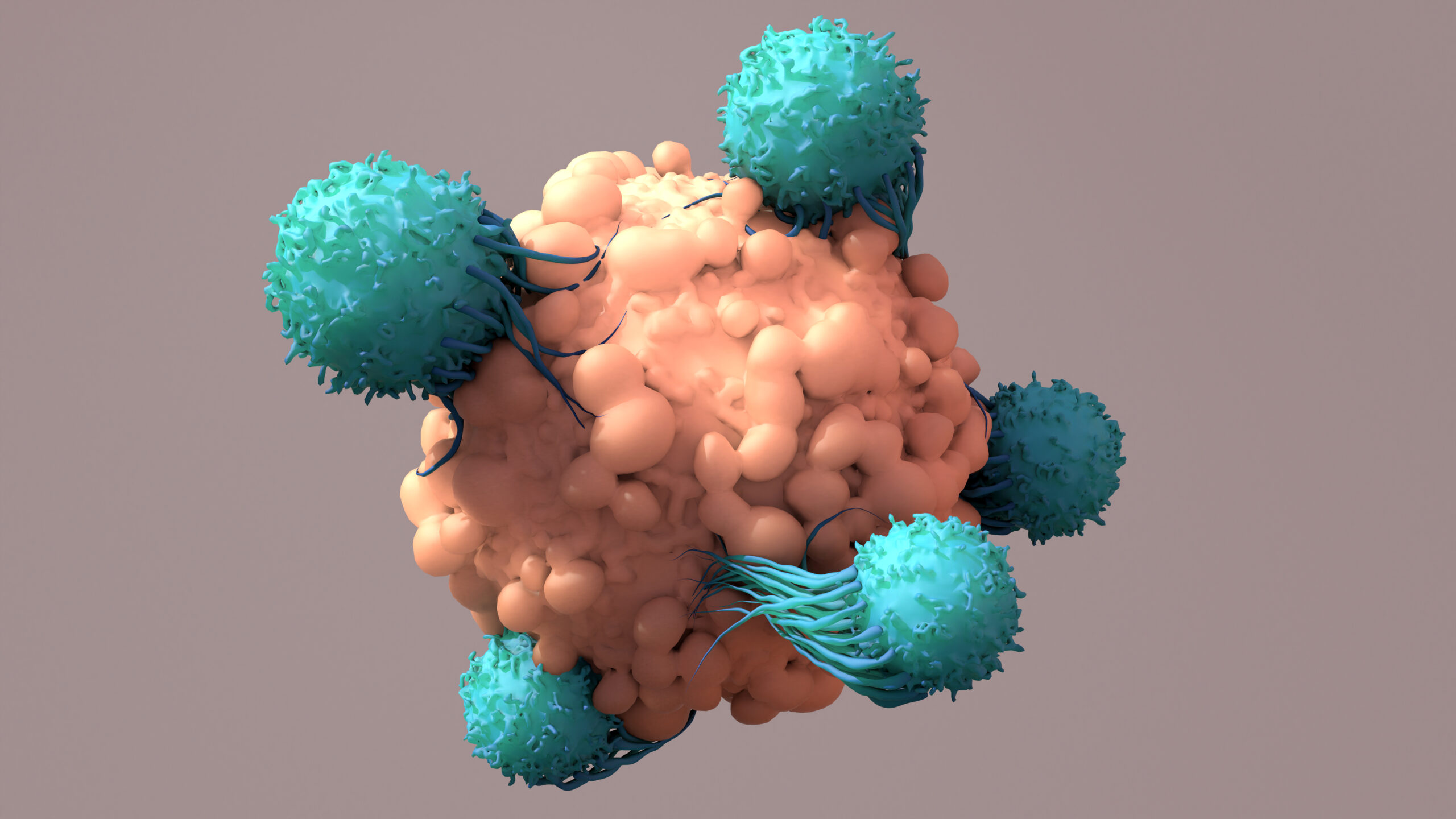

The Genentech team has been working on using this natural process to create methods of treating malignant tumours. They partnered with Adaptive Biotechnologies to engineer activated T-cells with the right type of receptors to recognise tumour cells. This means, in theory, that such engineered T-cells could be reintroduced into the body to accelerate the process by which T-cells find and kill solid tumour cells, a game changer for the immunotherapy space.

Zill explained that there are a handful of approaches to T-cell therapy in clinical development, the furthest along of which being CAR-T therapy. The TCR-T approach could be used in similar types of therapies to be more sensitive to the tumour antigens. It is like circulating the mugshot of a particularly prolific criminal, so the police on patrol know what to look out for.

The targeting of tumour cells is HLA (the genes responsible for encoding the MHC proteins on the surface of the cells) dependent, which means you have to consider a specific epitope and MHC allele. Zill focused on using this technology to target antigens that are presented on these types of cancer cells. Therefore, to make such treatments broadly applicable, the HLA alleles that they consider should be as common as possible.

Zill explained that there are many different neoantigens they could use, which makes it “a pretty crowded space”. But he said the main neoantigens of interest result from tumour development. They typically occur in a subset of cancer patients but can be prevalent across cancer indications.

Reprogramming T-cells to Find and Kill Tumour Cells

The shared approach

The Genentech and Adaptive Biotechnologies teams are working on two approaches for this technology: shared and individual. Their shared approach works by first finding out which tumour associated antigens (TAAs) are of interest to target. Then, this helps them understand which epitopes are good targets for the TCRs.

Next, the team must determine which TCRs will recognise the tumour antigens of interest. But this can be an arduous process; Zill pointed out: “The reason that identifying specific neoantigen reactive TCRs is difficult is because TCRs are very diverse overall. So, you really need a powerful high-throughput assay to do this.”

That’s where Adaptive Biotechnologies comes in—they use their MIRA assay technology to identify which TCRs would recognise the antigens they are targeting. The TCRs that they assay are derived from a naïve repertoire of T-cells from healthy donors. When they have identified a TCR that works, the genetic sequence for that TCR can be encoded into the patient’s T-cells to identify tumour cells correctly.

Therefore, the team can build a library of TAA–TCR working relationships which are then used to create an off-the-shelf solution, matching TCRs to existing cancer mutations. They could perform apheresis on the patient, isolate their T-cells, then gene-edit those T-cells to present the relevant TCR, expand them, and infuse them back into the patient.

The individualised approach

The individualised approach is similar to the shared approach but targets private antigens. “The vast majority of neoantigens are private to an individual patient’s tumour”, explained Zill, “and have unknown functional consequences.”

The ultimate goal is to identify neoantigenic TCRs using Adaptive’s MIRA assay to screen each cancer patient’s repertoire as part of the upstream process in an entirely customised way. With this done, they can then conduct the TCR gene-editing process the same way as the shared antigen process.

What Has Genentech Learned from TCR-T?

Engineered T-cell therapies such as TCR-T have the highest potential in attacking solid tumours. Along with this, it allows clinicians to focus upon antigens that are proven to have high immunogenicity and tumour specificity.

The technology Genentech is developing with Adaptive Biotechnologies takes advantage of these features. This has led to a technique that ensures the fast discovery of neoantigen reactive TCRs in both shared and private settings. Due to the promising nature of this technology, Zill said that the team envisioned in the future “deploying armies of patient-specific engineered T-cells that can be customised to the indication and various genomic factors of the patient's tumour.”

To be the first to learn about these innovative methods as they are implemented, sign up for our Immuno content monthly newsletter. Why not also sign up to attend Oxford Global’s next in-person Immuno UK conference, to track all the developments in immuno-oncology?