The STING in Immunotherapy’s Tail

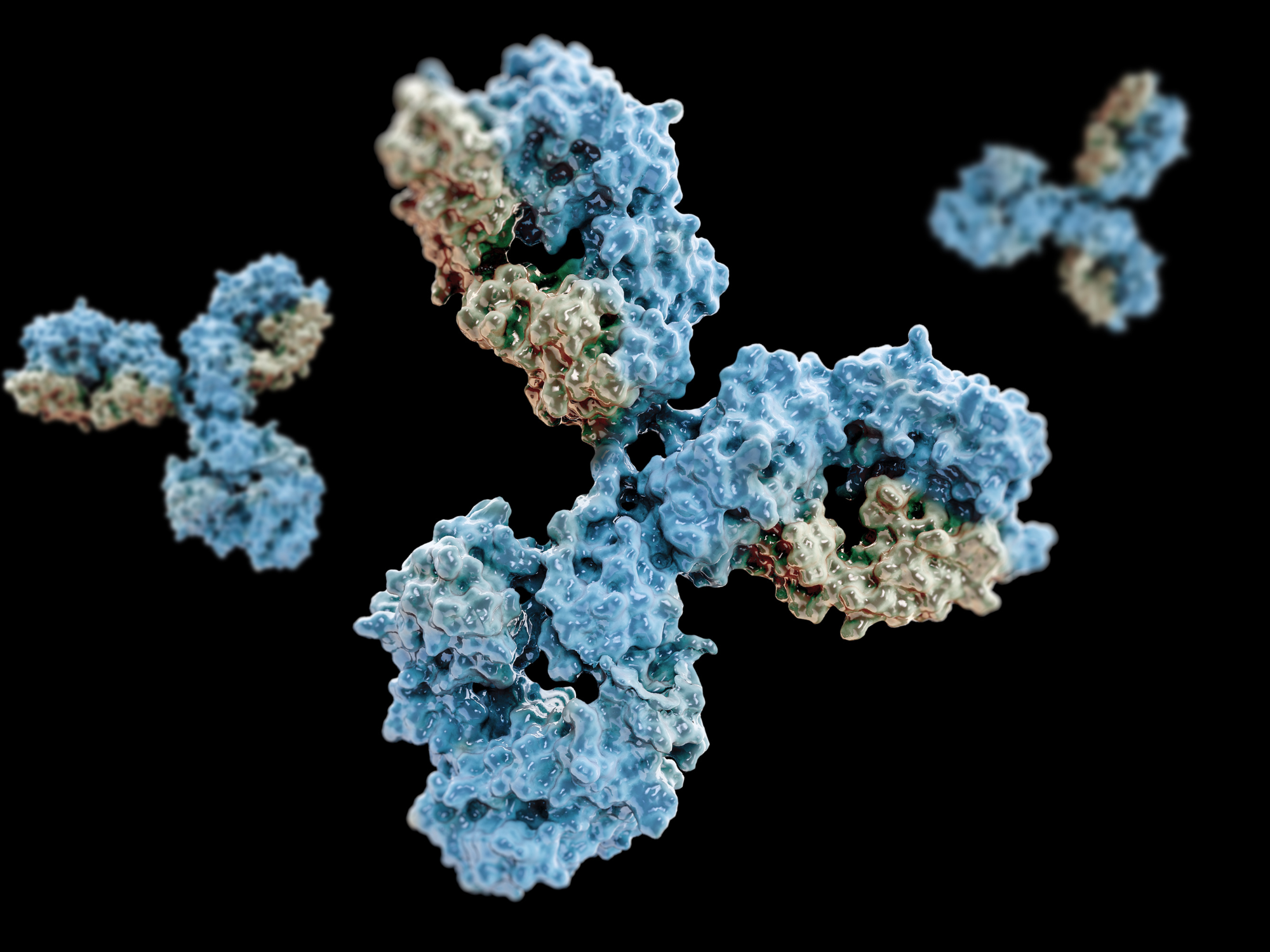

Immunotherapy revolutionised the nature of cancer treatment. Yet, a high percentage of patients do not respond to the treatment, as the hostile environment surrounding tumours is an obstacle to effective immune responses. The STimulator of INterferon Genes (STING) protein has garnered significant interest in the face of this challenge, as its capacity to stimulate multiple parts of the immune system was thought to potentially be the key to overcoming these obstacles. Firms including Eisai and Takeda have already studied how STING agonists impact multiple cancers, including advanced solid tumours.

- Is Your WASH Causing Inflammation? Protein Complex Linked to Inflammatory Conditions

- Eisai’s Alzheimer’s Drug Offers New Hope

- Why We Develop Autoimmunity: Hyperstimulation of Genetically Prone Subjects

However, whilst STING agonists have shown promise as mono- and adjunctive therapies during preclinical research, there has been a consistent failure to see these promises played out during clinical research. The study published last week by the University of North Carolina’s (UNC) Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center offers insight into why these repeated failures have occurred.

The researchers, working first with preclinical pancreatic cancer scenarios and later expanding to other solid tumours, including triple-negative breast cancer and melanoma, somewhat surprisingly found that STING agonists increased the production of regulatory B cells. These white blood cells actually suppress anti-cancer immunity rather than increasing it, significantly hindering tumour immunotherapy.

More specifically, these regulatory B cells secrete interleukin-35 (IL-35), an anti-inflammatory cytokine which can lead to "multiprong immunosuppression which is a hallmark of treatment-resistant cancers, such as pancreatic cancer”, Yuliya Pylayeva-Gupta, co-author of the study, explained. IL-35 impedes anti-tumour responses by suppressing the growth of natural killer cells (immune cells which attack tumours).

STING agonists increased the production of regulatory B cells. These white blood cells actually supress rather than increase anti-cancer immunity

Thus, these findings reveal that STING-activated responses are not crucial to natural killer cell function, as previously believed. Rather, the stimulation of IL-35 production directly restricts natural killer cell function, which one researcher, Sirui Li, described as a “previously unprecedented counter-scenario.”

So, what comes next? The researchers found that in mouse models, a combination of STING agonists with antibodies to block IL-35 led to a significant reduction in tumour growth compared to either STING agonists or the IL-35 antibody in isolation. They have therefore submitted a patent application for the dual therapy. They are now seeking to establish whether targeting STING and IL-35 with this experimental combination therapy will benefit humans.

Join Oxford Global’s annual Biologics UK: In-Person event today. This 3-day conference brings together a panel of prominent leaders and scientists, sharing new case studies, innovative data, and exciting industry outlooks.

Get your weekly dose of industry news here and keep up to date with the latest ‘Industry Spotlight’ posts. For other Biologics content, please visit the Biologics Content Portal.