The Challenges Facing Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Immuno-Oncology

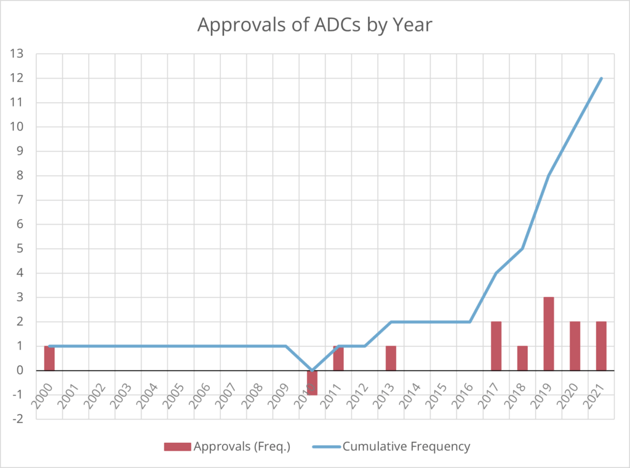

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), antibodies that target cancer cells to deliver a cytotoxic payload, have gained a recent popularity in the immuno-oncology space. Evidenced by a string of FDA approvals since 2017, the idea of targeted delivery of anti-cancer drugs has taken off. At the time of writing, 12 ADCs have received market approval, and there are many, many more in development. As Mahendra Deonarain, Chief Executive and Science Officer of Antikor said at Immuno Week Online 2021, “now we are at last, starting to see the fruits of our labour.”

Deonarain moderated our panel discussion titled Developing Antibody Drug Conjugates for Immuno-Oncology, which also welcomed Armin Sepp, Scientific Leader and GSK Fellow at GSK.

“ADCs were not particularly fashionable ten years ago,” said Deonarain, “even though they had been worked on for over 30 years.” Now, as the field starts to see approvals rise, researchers have set their sights on making ADCs better and more applicable to a wider variety of cancer indications. “Product approvals have been restricted to certain types of cancers,” Deonarain continued, mentioning lymphomas, breast cancers, and leukaemia, among others. “Other types of cancers are still pretty poorly served by ADC products – why is that?” he then asked.

Deonarain said that ADCs needed to be more applicable to challenging tumour environments. “ADCs are very complicated machines,” he pointed out, this is due to their complex structure: antibody, payload, and linker. More factors that can affect whether or not an ADC is successful include choice of target, rate of internalisation, mechanism of trafficking, location of drug release, bystander effects, potency, and tolerability.

What to Expect from the Future of ADCs

This brought the discussion to an audience question. Perhaps looking at what has made ADCs successful in the past will be a clue as to what will make them more effective in the future. “Do we need to play around with the actual conjugate itself?” asked Deonarain, “or do we need to focus more on harnessing the immune system?” Some therapies have combined ADCs with immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Another technique has been to conjugate with payloads that are not cytotoxic, but rather stimulate the immune system.

“Time matters”

Joining the discussion, Sepp commented that the majority of drugs that have reached the clinic treat haematological cancers and target T cells and B cells. “There is a very good reason for this,” he explained, “whatever is in the blood is easier to access.” IV administration leads to uniform distribution throughout the entire vasculature within about five to six minutes. In contrast, if the target is not in the blood, it can take three days for the antibody to enter the steady state as it circulates throughout the tissue. “Time matters,” affirmed Sepp.

Deonarian commented that because T and B cells are easier to target, an approach by ADC therapeutics has been to deplete Treg cells in order produce an immune response which he said seemed “like a good approach for solid tumours.” Although the goal is still to treat a solid malignancy, those lymphocytes are more in reach, effectively launching an indirect attack at the cancer.

Another issue that Sepp brought to light was on-target, off-tumour toxicity. “Obviously HER2 is on tumour cells, but it is also expressed elsewhere in the body,” he explained. Sepp added that the pharmacokinetics were also dose dependent: “1mg/kg, the half-life was just about two days.”

Sepp also touched on the problem that tumour tissue is somewhat different from normal tissues: “The consensus seems to be that there is little to no lymphatic flow through solid tumour tissues.” Instead, according to Sepp, there are “badly deformed lymphatic-like structures” which means that any exchange is diffusion-driven only and the concentration gradient is very slow. Adding to this, Sepp said that even if there was some diffusion into the tumour tissue, it will only be taken up by the first layer of tumour cells – “and that’s it, it just doesn’t get any further than that.”

What are the Most Critical Reasons for Failure?

The audience then asked our panellists what the most critical reasons for failure of an ADC were. Outright, Deonarain answered “delivery failure, insufficient local potency, adverse effects, and mechanism resistance – these things are all sort of linked.” He went on to say that when administering an ADC to a patient, no matter how high the dose, it will always reach a point of insufficiency due to the adverse effects. Therein, delivery failure and reaching the maximum tolerated dose are related.

An issue with ADC failure brought up by Sepp was the fact that the therapeutic window was fairly narrow. “The IC50 on negative control cells is about 5 to 6 nM – the equivalent dose would be reached from about 0.01 mg/kg which is very difficult to maintain.” This means that there are two sources of negative safety concerns for ADCs:

First, the unavoidable fact that ADCs attach to normal bystander cells which express the target. And second, non-specific uptake and degradation of proteins in circulation via pinocytosis – “that’s how antibodies in general are turned over.” As Sepp explained, about 20% of antibodies that are taken over by endothelial cells or dendritic cells are degraded on the cell surface. “If the payload is very potent,” Sepp added, “that actually brings down the maximum tolerated concentration.”

The potential of ADCs to treat difficult cancers is clear. However, also clear are the challenges that researchers are working to overcome. Translating the modality to treat solid tumours is certainly a key concern and approaches such as stimulating the immune system with ADCs could help. Challenges like delivery, potency, and maximum tolerated dose are also distinctly present. As Deonarian pointed out, these issues can often be interlinked so further understanding about ADC mechanisms is also vital to disentangling them.

Gain valuable insights into the approaches impacting the immunotherapy field through 40+ outstanding presentations tackling key discussion points in immuno-oncology, immunology, and inflammation at Immuno UK: In Person.