A ‘New Age’ of Biomarker Technology? Understanding Identification & Validation of IO Biomarkers

Biomarker development in immuno-oncology (IO) is an important area of research that can help identify patients who are most likely to benefit from immunotherapy and other cancer treatments. However, the field of identifying and validating disease markers does have some hurdles to jump in its implementation. Discussing both the challenges and the future of biomarker identification in immuno-oncology were the expert panel at Immuno 2023’s panel discussion ‘Biomarker Identification & Validation in The New Age of Biomarker Technology.’

Considerations for an IO Biomarker Strategy

Erin Newburn, Senior Director of Field Applications Scientist at Personalis, said that one of the first things to consider when developing a biomarker strategy for immuno-oncology was the prospect of working with challenging sample types. In immuno-oncology, these sample types are typically tumour sections in FFPE (formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded). Further, if these strategies focus on utilizing RNA, this has historically been quite difficult for FFPE materials in particular, creating another challenge.

RELATED:

- Improving Patient Response Through Effective Biomarker Development

- Three Leading Perspectives on Biomarker Diagnostic Discovery in Immuno-oncology

- Perfecting Precision Medicine: The Promise of Biomarkers and Spatial Biology

Tumour content also presents another preanalytical challenge due to the fact that certain analyses are more difficult when tumour content is very low. Furthermore, the general ability for clinicians to obtain the proper amount of adequate material to perform a test is an obstacle. This is especially so in indications that affect the kidney or lung where core needle biopsy yields a very small amount of tissue.

Explaining the clinical perspective was Markus Templin, Head of Assay Development, NMI – Natural and Medical Sciences Institute at the University of Tübingen. He said that there were abundant promising and novel techniques but applying them in the clinic is not easy. Furthermore, interpreting sequencing data is difficult for clinicians. In Templin’s opinion, the biggest hurdle for clinical use of novel biomarkers is enabling the tools to make hard decisions and putting them in the hands of clinicians.

A ‘New Era’ of Biomarker Discovery and Validation?

In Newburn’s view, the field of biomarker validation and discovery has already entered a new era. She explained that the previous biomarker doctrine for targeted therapies was to utilise a “single gene, single analyte” approach. There has been fresh support for needing more multidimensional strategies to understand the complex interplay between the tumour and the tumour microenvironment.

These strategies include taking a multi-omic approach, using single metrics like tumour mutational burden (TMB) and neoantigen burden, and further considerations regarding the biology in question. For assessing tumour foreignness using neoantigen burden, Newburn said: “how relevant are those neoepitopes if they are not able to be properly presented to your immune system?” Tumour escape mechanisms should be considered as well.

Templin added that the vast number of mutations that are present means that it is not so easy to identify the responsible driver of malignancy. “If you do have functional data, and bring it together with the sequencing of mutation information, that will really change the game and make clinical decision making much easier.”

Using New Technologies for Biomarker Development

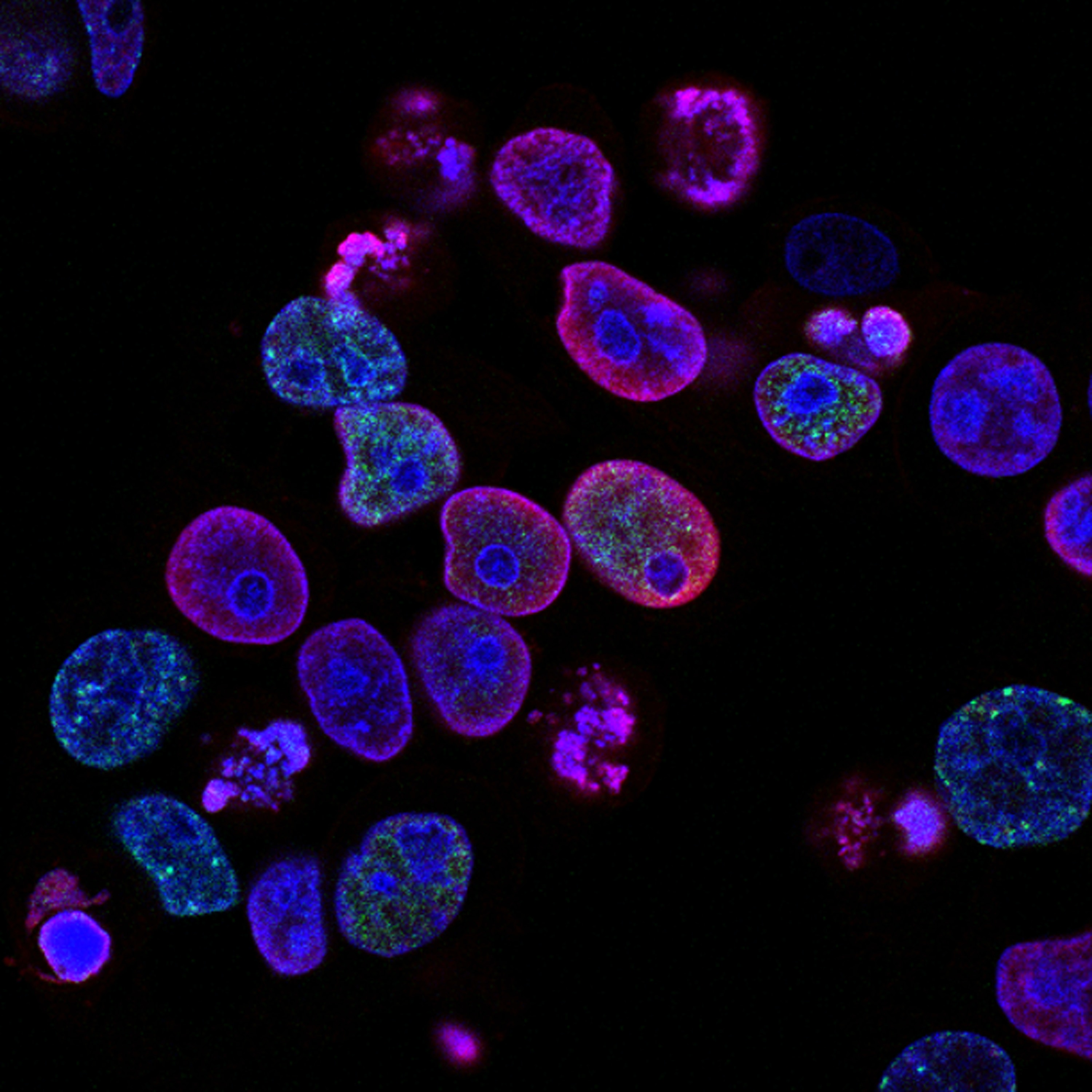

As technology for biomarker development and discovery advances, cellular and even subcellular screening has become a possibility. Spatial biology is one such technology of a particular interest to those working in biomarker development. Templin explained that the advantage of this biomarker strategy is that “the people who have to interpret the data are very often the pathologists who are used to looking at that kind of data.” Herein, those pathologists can bring their experience of the histology together with this new information.

Another consideration for fresh technologies for biomarker development – like spatial omics – are their minimum requirements. What should companies have to generate in order to make these tools useful for biomarker discovery? There are multiple factors that must be considered: tissue accessibility, performance on tissue, and robustness, to name a few.

Another difficulty that Templin outlined is the fact that “the decision-making chain in the clinic is strict, well established, and unlikely to change.” This is an overarching concern with the adoption of new technologies in the clinic; in order to do so, they need to be very well established and have proven use in centres. Templin said: “this will take a lot of time, but once it has happened, the pathologists are very open to integrating this information into their data and expounding clinically how to treat the patient.”

Newburn added that a solid understanding of the ideal sensitivity and specificity of an assay is required when trying to implement next generation sequencing technologies. Furthermore, the data for these assessments needs to be harmonised across platforms. “For example, there are a lot of different platforms out there that provide a tumour mutational burden (TMB) assessment – are they harmonised across platforms? This takes a lot of time and study.” For instance, the Friends of Cancer Research worked tirelessly to harmonise data across their platforms.

For more insights into immuno-oncology, as well as commentaries, discussion group reports, and Q&As, sign up for our Immuno newsletter to receive monthly highlights. Are you interested in more about biomarkers in immuno-oncology? Why not come along to our next Immuno UK and Biomarkers UK conferences this year.