The Bioavailability of Oral PROTAC Molecules for ER+ Breast Cancer

Estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer is a type of breast cancer in which its cancer cells have estrogen receptors. In ER+, malignant cells then use the hormone estrogen to grow. Here, E2 ligand estrogen binds to the estrogen receptor and acts as an agonist which activates transcription of downstream genes that are implicated in breast cancer.

The standard method of care for this kind of cancer uses a drug that blocks this mechanism called a fulvestrant. Fulvestrants are selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs), agonists that prevent the E2 ligand from binding to the receptor and ultimately degrades the ER.

There are many fulvestrants of this kind that exist as therapies, although they usually involve painful injections and there is no oral substitute. AstraZeneca is one company that have been looking for compounds that could therapeutically use this mechanism with suitable oral bioavailability.

Thomas Hayhow, Associate Principal Scientist at AstraZeneca presented to Oxford Global’s ‘Oral PROTAC and PK/PD Profiling’ discussion group an account of his team’s experience with ER degraders’ oral bioavailability. He recounted the development of AstraZeneca’s compound AZ’6421, an oral PROTAC with an in-vitro–in-vivo disconnect. They have been trying to push towards already existing compounds that antagonise and degrade ERs.

Beyond SERDs and Pursuing PROTACs

The team went out in search of whether PROTACs were viable as an oral drug. They used their earlier SERD (AZD’9496) as a starting point when designing the compound. This was because they knew that it bound to ER nicely. They also used VHL as the E3 ligase binder, a common choice for PROTACs.

The next task was to investigate what linker they wanted to use to tie the two parts together. Hayhow explained that they had identified a linker that resulted in potent degradation but due to the high hepatocyte level in mouse models, it needed to be improved to be viable for oral delivery.

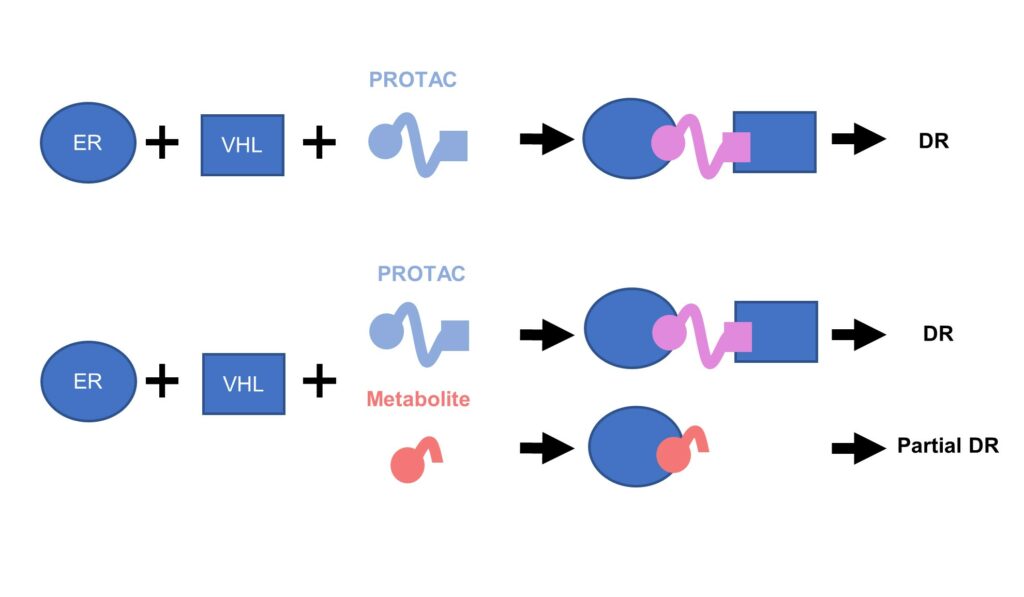

They named the compound AZ’6421, which showed quick degradation of ER in-vitro. To the team’s enthusiasm, the evidence showed that the molecule did indeed degrade via a PROTAC-induced mechanism rather than solely SERD degradation. However, there were a few hints of residual SERD-like degradation as well

The In-Vivo Problem

However, the AstraZeneca team found unexpected results when testing in-vivo. Given the in-vitro profiling, they experienced no increase in degradation as dosage increased. As Hayhow said, “in-vivo we saw no dose response.”

“In-vivo we saw no dose response.”

There were a number of issues that the team troubleshooted to work out what was going wrong. They found that the exposure of the drug in the tumour was adequate, the PD effect of the compound was similar and there were no differential on-target effects such as hypoxia. Therefore, the cause of the problem must be elsewhere.

Hayhow then explained that one theory as to the origin of this problem was that the degrader was experiencing competition from metabolites. Metabolites would curtail the efficiency of their PROTAC as they would take up the ER sites rather than their compound.

From another troubleshoot, this is indeed what they found. Metabolites were present at much higher free levels than the PROTAC itself and therefore, the metabolites seem to be “completely outcompeting the PROTAC,” said Hayhow.

Figure. 1 – Metabolite reduces ER degradation in-vivo.

In summary, Hayhow offered the following advice to designers of oral PROTACs: “watch out for metabolites! They can really ruin your PROTAC if you’re working in-vivo.” ER was one of the first PROTAC projects that AstraZeneca had undertaken, perhaps the first ever to go in-vivo. Although the compound itself showed some encouraging ER degradation in-vitro, it was unfortunately impaired by its metabolite problem in-vivo.

Key Parameters for PROTACs to Consider Beyond the Rule of Five

Another attendee raised an interesting question to the group. They asked, when designing PROTACs, what are the key parameters that you need to be aware of in terms of bioavailability? Lipinski’s rule of five has been somewhat of a gold-standard for drug design, but does it necessarily translate to the discovery of PROTACs?

Hayhow described that there were various publications that have discussed things to keep in mind when designing ‘beyond-rule of five’ drugs, but says “in some ways, I don’t think that PROTACs are particularly special molecules other than the fact that they are a bit bigger than other small molecules.”

“In some ways, I don’t think that PROTACs are particularly special molecules other than the fact that they are a bit bigger than other small molecules”

“So really, trying to stick as close to the rule of five as you can is not a bad place to be,” Hayhow continued. Hayhow maintained that keeping the molecular weight and number of rotatable bonds of your molecule as low as possible was good to keep in mind.

Particularly, he stressed that reducing hydrogen bond donors was vital. He gave here the example of VHL, “when embedded, it usually has got two or three hydrogen bond donors which can be enough to shut down bioavailability all-together— putting three of them on an extra-large compound is not putting yourself in good-stead for bioavailability.”

Join and network with over 400 industry leaders at our renowned Drug Discovery Summit in Berlin, where we will address the latest advancements in target identification, validation and HIT optimisation.