Getting PROTACs into the Clinic: The Challenges

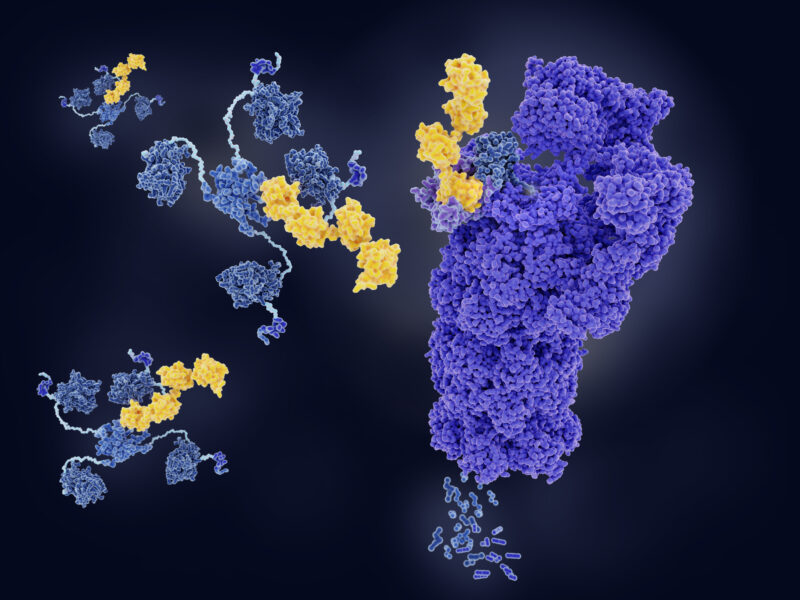

Proteolysis-targeting chimaeras (PROTACs) bring together E3 ligases with targeted proteins, effectively ‘hijacking’ the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), which degrades the unwanted proteins back down into their amino acids to be used again. Using cell-active degraders as therapeutics shows promise, but with only two clinical candidates currently, the challenge is turning this pioneering science into usable drugs in the clinic.

At Oxford Global’s 2021 Protein Degradation Virtual Symposium, our panel provided an exciting exchange on the challenges of bringing PROTACs into the clinic and solutions to overcome these problems. Entitled “Strategies Beyond the Proof-of-Concept Molecules,” we saw a discussion on a broad range of topics in PROTAC advancement. Topics included understanding its unique PD/PK relationship, developing oral solutions to the delivery of PROTACs in higher species (towards human endpoints), and the ability to overcome resistance.

Making More Predictable In Vivo Profiles

“We need to find ways to characterise oral administration routes better, especially in bridging the gap between rodents and higher species”

Delivering PROTACS orally is a key goal in the field. Unfortunately, their bifunctional nature often leads to properties unsuitable for small molecule oral drugs. Markus Schade, Principal Investigator at AstraZeneca explains that “we need to find ways to characterise oral administration routes better, especially in bridging the gap between rodents and higher species.” Although plenty of in vitro and rodent PK data are available for PROTACs, higher species and human PK data are very scarce, despite an encouraging eight oral PROTACs having reached clinical trials so far.

Schade considered that for some mechanisms of action, such as those on immune cells, PROTAC effects on primary human tissue could be studied ex vivo, as exemplified for a clinical stage, oral PROTAC from Kymera Therapeutics. Nonetheless, much more needs to be learned about PROTAC coverage of other human tissues.

There was a consensus from the panel that other administration routes should also be tested. But still, this does not necessarily overcome the PD/PK disconnect challenge. Schade commented that sharing more knowledge in the scientific community would ultimately help them overcome some of these challenges.

Are Broad Patents Restrictive to Research?

The panel then considered whether the landscape of patents in the field has hindered research. Many of the patents for PROTAC technologies have broad claims, so scientists—especially scientists working for smaller companies—can find navigating around those patents restricts their research.

One senior representative from a leading pharma company commented that a more open attitude towards sharing data would benefit the field. She says that traditional small molecule development optimisation has “decades of experience” behind it, whereas “the degrader field is very young compared to that.” She concluded that sharing data would help with this.

"There are some broad patent claims, but the number of claims that get granted is different”

In contrast, Ian Churcher, Chief Scientific Officer of Amphista Therapeutics, believed that the patent landscape might not be as restrictive as some might think. “There are some broad patent claims, but the number of claims that get granted is different,” he said. Due to the plurality of ways PROTACs can be successfully designed, Churcher thought there was plenty of room for novel developments.

Churcher did agree, however, that scientists were not able to share enough knowledge across the field but did not think the fault lay with patents. Instead, he said the “bigger hindrance is that this ‘know-how’ is viewed as proprietary and therefore not shared.”

Yet another perspective was then given by Schade, who commented on how special many PROTAC patent applications are from a chemistry perspective: “Often, it starts with a public, well-profiled small molecule target binder, including approved drug molecules. The other end of the PROTAC is then decorated with another well-known E3 ligase binder, which leaves merely the linker and its attachment points for creativity.”

Schade recalled how at the height of research parallel to the human genome project, companies would patent human genes very broadly for “all sorts of therapeutic applications” and noted the some similarity in the PROTAC space.

The Problem of Resistance: Are PROTACs a Double-Edged Sword?

A significant challenge that may prevent PROTACs from giving durable clinical responses is their high levels of potential for emergence of resistance. Our panel, therefore, considered the pressing question of building upon the advantages of PROTACs while simultaneously overcoming resistance mechanisms.

However, one representative said this was difficult to predict: “It would be nice to have some more flexibility—a co-existing scheme of different E3 ligases for the same target—doubling the chance of resistance. An advantage of PROTACs is that you don’t need a lot of affinity to your protein of interest.”

Another leading scientist concurred that there have only been in vitro studies at very high doses, so predicting how a PROTACs effect will translate to a particular patient is unlikely. To help overcome resistance, she says, “you could use PROTACs to remove the target as quickly as possible; you may not need very high doses. But for the moment, this is all hypothesis.”

Concluding thoughts were shared by Churcher, who says the field of gene editing has potential to help inform target choice and predict clinical responses. He described the increasing amount of emerging CRISPR screening data and how they could use it to understand a PROTAC’s potential susceptibilities to resistance. However, this only gets you part of the way there, “there’s not enough PROTAC clinical data to translate it into the clinic yet to understand the size of any problem.”

We have seen a variety of projects for those working in PROTACs that could help bring the field forward into the clinical stages of development. Although PROTAC development presents several potential challenges, our panel has shown that each challenge comes with its own opportunities. We are excited to see more PROTACs making their way into clinical trials in the near future.

Are you excited about the horizons of drug discovery and development? Join us at our next Discovery Europe conference to see our expert panellists in person. Sign up for our newsletter to receive highlights from our discovery content portal each month.